- What are the benefits and dangers of generalizations?

- What makes stereotyping illogical?

- Beware: we often make snap judgments before thinking through things. Then when we do think through things, we just wind up rationalizing our snap judgments.

Thursday, September 27, 2012

Our Inductive Minds

Here are some more thoughtful links on inductive reasoning.

Labels:

as discussed in class,

inductive,

links

Wednesday, September 26, 2012

Inductioneering

Here are two dumb things about inductive arguments. First, a video of comedian Lewis Black describing his failure to learn from experience every year around Halloween:

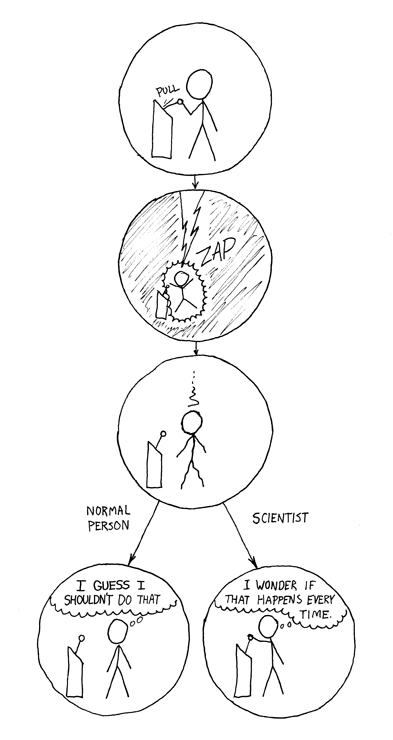

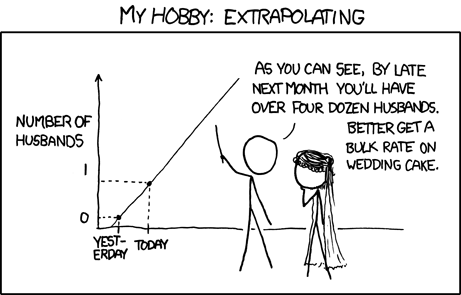

Next, this stick figure comic offers a pretty bad argument. Why is it bad? (Let us know in the comments!)

Next, this stick figure comic offers a pretty bad argument. Why is it bad? (Let us know in the comments!)

Tuesday, September 25, 2012

Quiz You Once, Shame on Me

The first quiz will be held at the beginning of class on Thursday, September 27th. You will have about 25 minutes to take it.

There will be a multiple choice section, a section on understanding arguments, a section on evaluating deductive arguments, and a section where you provide examples of specific kinds of arguments. Basically, it will look like a mix of the homework, extra credit, and group work we've done in class so far.

The quiz is on what we have discussed in class from chapters 6, 8, and part of 7 of the textbook. Specifically, here's a lot of the stuff we've talked about in class so far that I expect you to know for the quiz:

There will be a multiple choice section, a section on understanding arguments, a section on evaluating deductive arguments, and a section where you provide examples of specific kinds of arguments. Basically, it will look like a mix of the homework, extra credit, and group work we've done in class so far.

The quiz is on what we have discussed in class from chapters 6, 8, and part of 7 of the textbook. Specifically, here's a lot of the stuff we've talked about in class so far that I expect you to know for the quiz:

- definitions of: logic, reasoning, argument, support, sound, valid, deductive, inductive

- understanding arguments

- evaluating arguments (truth and support!)

- deductive args (valid & sound)

- inductive args (there will only be a little on this, based on Tuesday's class)

Labels:

as discussed in class,

assignments,

deductive,

inductive,

links,

understanding

Tuesday, September 18, 2012

Homework #1: Deductive Arguments

Homework assignment #1 is due at the beginning of class on Thursday, September 20th. It's worth 3% of your overall grade. The assignment is

to complete the worksheet I hand out in class.

If you don'tt get it in class, you can download the worksheet here. Or, if you can't download it, here are the questions on the worksheet:

If you don'tt get it in class, you can download the worksheet here. Or, if you can't download it, here are the questions on the worksheet:

DIRECTIONS: Provide original examples of the following types of arguments (in premise/conclusion form), if possible. If it is not possible, explain why.

1. A valid deductive argument with one false premise.

2. An invalid deductive argument with all true premises.

3. An unsound deductive argument that is valid.

4. A sound deductive argument that is invalid.

MULTIPLE CHOICE: Circle the correct response. Only one answer choice is correct.

5. If a deductive argument is unsound, then:

a) it must be valid.

b) it must be invalid.

c) it could be valid or invalid.

6. If a deductive argument is unsound, then:

a) at least one premise must be false.

b) all the premises must be false.

c) all the premises must be true.

d) not enough info to determine.

7. If a deductive argument is unsound, then:

a) its conclusion must be false.

b) its conclusion must be true.

c) its conclusion could be true or false.

8. If a deductive argument’s conclusion is true:

a) then the argument must be valid.

b) then the argument must be invalid.

c) then the argument could be valid or invalid.

9. If a deductive argument is sound, then:

a) it must be valid.

b) it must be invalid.

c) it could be valid or invalid.

10. If a deductive argument is sound, then:

a) at least one premise must be false.

b) all the premises must be false.

c) all the premises must be true.

d) not enough info to determine.

11. If a deductive argument is sound, then:

a) its conclusion must be true.

b) its conclusion must be false.

c) its conclusion could be true or false.

12. If a deductive argument’s conclusion is false:

a) then the argument must be valid.

b) then the argument must be invalid.

c) then the argument could be valid or invalid.

Labels:

as discussed in class,

assignments,

deductive

Sunday, September 16, 2012

Evaluating Deductive Arguments Handout

Here are the answers to the handout on evaluating deductive arguments that we did as group work in class.

1) All bats are mammals.

All mamammals live on earth.

All bats live on earth.

All frogs are amphibians.

No frogs are humans.

All bats have wings.

All mammals have wings.

All bearded people are mean.

Some dads are mean.

Some people ate tacos yesterday.

Oprah Winfrey ate tacos yesterday.

All humans are mammals.

All students in here are humans.

9) All hornets are wasps.

9) All hornets are wasps.

All wasps are insects.

All insects are scary.

All hornets are scary.

Sean is singing right now.

Students are cringing right now.

Sean isn't singing right now.

Students aren't cringing right now.

Most humans are shorter than 7 feet tall.

Most students in here are shorter than 7 feet tall.

Bush was either a great prez or the greatest prez.

Bush wasn’t the greatest prez.

Bush was a great prez.

Students are cringing right now.

Sean is singing right now.

Students aren't cringing right now.

Sean isn't singing right now.

Life isn't meaningless.

There is a God.

1) All bats are mammals.

All mamammals live on earth.

All bats live on earth.

P1- true

P2- true

support- valid

overall- sound

2) All email forwards are annoying.

Some email forwards are false.

Some annoying things are false.

All females in this class are humans.

All males in this class are females.

Some email forwards are false.

Some annoying things are false.

P1- questionable ("annoying" is subjective)3) All males in this class are humans.

P2- true

support- valid (the premises establish that some email forwards are both annoying and false; so some annoying things [those forwards] are false)

overall- unsound (bad first premise)

All females in this class are humans.

All males in this class are females.

P1- true4) No humans are amphibians.

P2- true

support- invalid (the premises only tell us that males and females both belong to the humans group; we don't know enough about the relationship between males and females from this)

overall- unsound (bad support)

All frogs are amphibians.

No frogs are humans.

P1- true5) All bats are mammals.

P2- true

support- valid (the premises say that frogs belong to a group that humans can't belong to, so it follows that no frogs are humans)

overall- sound

All bats have wings.

All mammals have wings.

P1- true6) Some dads have beards.

P2- true (if interpreted to mean "All bats are the sorts of creatures who have wings.") or false (if interpreted to mean "Each and every living bat has wings," since some bats are born without wings)

support- invalid (we don't know anything about the relationship between mammals and winged creatures just from the fact that bats belong to each group)

overall- unsound (bad support)

All bearded people are mean.

Some dads are mean.

P1- true7) Oprah Winfrey is a person.

P2- questionable ("mean" is subjective)

support- valid (if all the people with beards were mean, then the dads with beards would be mean, so some dads would be mean)

overall- unsound (bad 2nd premise)

Some people ate tacos yesterday.

Oprah Winfrey ate tacos yesterday.

P1- true8) All students in here are mammals.

P2- true (you might not have directly seen anyone eat tacos, but you have a lot of indirect evidence... with all the Taco Bells, Don Pablos, etc., surely lots of people ate tacos yesterday)

support- invalid (the 2nd premise only says some ate tacos; Oprah could be one of the people who didn't)

overall- unsound (bad support)

All humans are mammals.

All students in here are humans.

P1- true

P2- true

support- invalid (the premises only tell us that students and humans both belong to the mammals group; we don't know enough about the relationship between students and humans from this; for instance, what if a dog were a student in our class?)

overall- unsound (bad structure)

9) All hornets are wasps.

9) All hornets are wasps.All wasps are insects.

All insects are scary.

All hornets are scary.

P1- true!10) If Sean sings, then students cringe.

P2- true

P3- questionable ("scary" is subjective)

support- valid (same structure as in argument #1, just with an extra premise)

overall- unsound (bad 3rd premise)

Sean is singing right now.

Students are cringing right now.

P1- questionable (since you haven't heard me sing, you don't know whether it's true or false)11) If Sean sings, then students cringe.

P2- false

support- valid

overall- unsound (bad premises)

Sean isn't singing right now.

Students aren't cringing right now.

P1- questionable (again, you don't know)12) All students in here are humans.

P2- true

support- invalid (from premise 1, we only know what happens when Sean is singing, not when he isn't singing; students could cringe for a different reason)

overall- unsound (bad 1st premise and structure)

Most humans are shorter than 7 feet tall.

Most students in here are shorter than 7 feet tall.

P1- true13) (from Stephen Colbert)

P2- true!

support- invalid (the premises state a strong statistical generalization over a large population, and the conclusion claims that this generalization holds for a much smaller portion of that population; even though it's likely that most students in here are, in fact, shorter than 7 feet tall, it nevertheless could be true that the humans in here are a statistical anomaly)

overall- unsound (bad support)

Bush was either a great prez or the greatest prez.

Bush wasn’t the greatest prez.

Bush was a great prez.

P1- questionable ("great" is subjective)14) If Sean sings, then students cringe.

P2- questionable ("great" is subjective)

support- valid (it's either A or B; it's not A; so it's B)

overall- unsound (bad premises)

Students are cringing right now.

Sean is singing right now.

P1- questionable (again, you don't know)15) If Sean sings, then students cringe.

P2- false

support- invalid (from premise 1, we only know that Sean singing is one way to guarantee that students cringe; just because they're cringing doesn't mean Sean's the one who caused it; again, students could cringe for a different reason)

overall- unsound (bad premises and structure)

Students aren't cringing right now.

Sean isn't singing right now.

P1- questionable (again, you don't know)16) If there is no God, then life is meaningless.

P2- true

support- valid

overall- unsound (bad 1st premise)

Life isn't meaningless.

There is a God.

P1- questionable (that's not an obvious claim to prove or disprove)

P2- questionable (again, that's not an obvious claim to prove or disprove)

support- valid (the same structure as argument #15)

overall- unsound (bad premises)

Saturday, September 15, 2012

An Argument's Support

One of the trickier concepts to understand in this course is the structure (or

support) of an argument. This is a more detailed explanation of

the term (it's the same as the handout). If you've been struggling

to understand this term, the following might help you.

An argument's structure is its underlying logic; the way the premises and conclusion logically relate to one another. The structure of an argument is entirely separate from the actual meaning of the premises. For instance, the following three arguments, even though they're talking about different things, have the exact same structure:

1) All tigers have stripes.

Tony is a tiger.

Tony has stripes.

2) All humans have wings.

Sean is a human.

Sean has wings.

3) All blurgles have glorps.

Xerxon is a blurgle.

Xerxon has glorps.

There are, of course, other, non-structural differences in these three arguments. For instance, the tiger argument is overall good, since it has a good structure AND true premises. The human/wings argument is overall bad, since it has a false premise. And the blurgles argument is just crazy, since it uses made up words. Still, all three arguments have the same underlying structure (a good structure):

All A's have B's.

x is an A.

x has B's.

Evaluating the structure of an argument is tricky. Here's the main idea regarding what counts as a good structure: the premises provide us with enough information for us to figure out the conclusion from them. In other words, the premises, if they were true, would logically show us that the conclusion is true. So, if you believed the premises, they would convince you that the conclusion is worth believing, too.

Note I did NOT say that the premises are actually true in a good-structured argument. Structure is only about truth-preservation, not about whether the premises are actually true or false. What's "truth preservation" mean? Well, truth-preserving arguments are those whose structures are such that if you stick in true premises, you get a true conclusion.

The premises you've actually stuck into this particular structure could be good (true) or bad (false). That's what makes evaluating an arg's structure so weird. To check the structure, you have to ignore what you actually know about the premises being true or false.

Good Structured Arguments

If we assume that all the premises are true, then the conclusion will also be true for an argument to have a good structure. Notice we are only assuming truth, not guaranteeing it. Again, this makes sense, because we’re truth-preservers: if the premises are true, the conclusion that follows will be true.

EXAMPLES:

1) All humans are mammals.

All mammals have hair.

All humans have hair.

2) If it snows, then it’s below 32 degrees.

It is snowing right now.

It’s below 32 degrees right now.

3) All humans are mammals.

All mammals have wings.

All humans have wings.

4) Either Yao is tall or Spud is tall.

Yao is not tall.

Therefore, Spud is tall.

Even though arguments 3 and 4 are ultimately bad, they still have good structure (their underlying form is good). The second premise of argument 3 is false—not all mammals have wings—but it has the same exact structure of argument 1—a good structure. Same with argument 4: the second premise is false (Yao Ming is about 7 feet tall), but the structure is good (it’s either this or that; it’s not this; therefore, it’s that).

To evaluate the structure, then, assume that all the premises are true. Imagine a world in which all the premises are true. In that world, are you able to figure out from the premises that the conclusion is also true? Or can you imagine a scenario in that world in which the premises are true, but the conclusion is still false? If you can imagine this situation, then the argument's structure is bad. If you cannot, then the argument is truth-preserving (inputting truths gives you a true output), and thus the structure is good.

Bad Structured Arguments

In an argument with a bad structure, you can’t draw the conclusion from the premises – the premises don’t give you enough information. Bad structured arguments do not preserve truth.

EXAMPLES:

1) All humans are mammals.

All whales are mammals.

All humans are whales.

2) If it snows, then it’s below 32 degrees.

It doesn’t snow.

It’s not below 32 degrees.

3) All humans are mammals.

All students in our class are mammals.

All students in our class are humans.

4) Either Yao is tall or Spud is short.

Yao is tall.

Spud is short.

Even though arguments 3 and 4 have all true premises and a true conclusion, they are still have a bad structure, because their form is bad. Argument 3 has the same exact structure as argument 1—a bad structure (it doesn’t preserve truth).

Even though in the real world the premises and conclusion of argument 3 are true, we can imagine a world in which all the premises of argument 3 are true, yet the conclusion is false. For instance, imagine that our school starts letting dogs take classes. The second premise would still be true, but the conclusion would then be false.

The same goes for argument 4: even though Spud is short (Spud Webb is around 5 feet tall), this argument doesn’t guarantee this. The structure is bad (it’s either this or that; it’s this; therefore, it’s that, too.). We can imagine a world in which Yao is tall, the first premise is true, and yet Spud is tall, too.

An argument's structure is its underlying logic; the way the premises and conclusion logically relate to one another. The structure of an argument is entirely separate from the actual meaning of the premises. For instance, the following three arguments, even though they're talking about different things, have the exact same structure:

1) All tigers have stripes.

Tony is a tiger.

Tony has stripes.

2) All humans have wings.

Sean is a human.

Sean has wings.

3) All blurgles have glorps.

Xerxon is a blurgle.

Xerxon has glorps.

There are, of course, other, non-structural differences in these three arguments. For instance, the tiger argument is overall good, since it has a good structure AND true premises. The human/wings argument is overall bad, since it has a false premise. And the blurgles argument is just crazy, since it uses made up words. Still, all three arguments have the same underlying structure (a good structure):

All A's have B's.

x is an A.

x has B's.

Evaluating the structure of an argument is tricky. Here's the main idea regarding what counts as a good structure: the premises provide us with enough information for us to figure out the conclusion from them. In other words, the premises, if they were true, would logically show us that the conclusion is true. So, if you believed the premises, they would convince you that the conclusion is worth believing, too.

Note I did NOT say that the premises are actually true in a good-structured argument. Structure is only about truth-preservation, not about whether the premises are actually true or false. What's "truth preservation" mean? Well, truth-preserving arguments are those whose structures are such that if you stick in true premises, you get a true conclusion.

The premises you've actually stuck into this particular structure could be good (true) or bad (false). That's what makes evaluating an arg's structure so weird. To check the structure, you have to ignore what you actually know about the premises being true or false.

Good Structured Arguments

If we assume that all the premises are true, then the conclusion will also be true for an argument to have a good structure. Notice we are only assuming truth, not guaranteeing it. Again, this makes sense, because we’re truth-preservers: if the premises are true, the conclusion that follows will be true.

EXAMPLES:

1) All humans are mammals.

All mammals have hair.

All humans have hair.

2) If it snows, then it’s below 32 degrees.

It is snowing right now.

It’s below 32 degrees right now.

3) All humans are mammals.

All mammals have wings.

All humans have wings.

4) Either Yao is tall or Spud is tall.

Yao is not tall.

Therefore, Spud is tall.

Even though arguments 3 and 4 are ultimately bad, they still have good structure (their underlying form is good). The second premise of argument 3 is false—not all mammals have wings—but it has the same exact structure of argument 1—a good structure. Same with argument 4: the second premise is false (Yao Ming is about 7 feet tall), but the structure is good (it’s either this or that; it’s not this; therefore, it’s that).

To evaluate the structure, then, assume that all the premises are true. Imagine a world in which all the premises are true. In that world, are you able to figure out from the premises that the conclusion is also true? Or can you imagine a scenario in that world in which the premises are true, but the conclusion is still false? If you can imagine this situation, then the argument's structure is bad. If you cannot, then the argument is truth-preserving (inputting truths gives you a true output), and thus the structure is good.

Bad Structured Arguments

In an argument with a bad structure, you can’t draw the conclusion from the premises – the premises don’t give you enough information. Bad structured arguments do not preserve truth.

EXAMPLES:

1) All humans are mammals.

All whales are mammals.

All humans are whales.

2) If it snows, then it’s below 32 degrees.

It doesn’t snow.

It’s not below 32 degrees.

3) All humans are mammals.

All students in our class are mammals.

All students in our class are humans.

4) Either Yao is tall or Spud is short.

Yao is tall.

Spud is short.

Even though arguments 3 and 4 have all true premises and a true conclusion, they are still have a bad structure, because their form is bad. Argument 3 has the same exact structure as argument 1—a bad structure (it doesn’t preserve truth).

Even though in the real world the premises and conclusion of argument 3 are true, we can imagine a world in which all the premises of argument 3 are true, yet the conclusion is false. For instance, imagine that our school starts letting dogs take classes. The second premise would still be true, but the conclusion would then be false.

The same goes for argument 4: even though Spud is short (Spud Webb is around 5 feet tall), this argument doesn’t guarantee this. The structure is bad (it’s either this or that; it’s this; therefore, it’s that, too.). We can imagine a world in which Yao is tall, the first premise is true, and yet Spud is tall, too.

Thursday, September 13, 2012

Extra Credit: Understanding a Long Argument

As mentioned in class, your next extra credit assignment is to read the following column by Paul Krugman in the New York Times:

Figure out Krugman's argument: what is his main point? What are his reasons supporting this main point? Paraphrase Krugman's argument in a clear premise/conclusion format and in your own words. Hand in your formal premise/conclusion version of Krugman's article at the beginning of class on Tuesday, September 18th.

Figure out Krugman's argument: what is his main point? What are his reasons supporting this main point? Paraphrase Krugman's argument in a clear premise/conclusion format and in your own words. Hand in your formal premise/conclusion version of Krugman's article at the beginning of class on Tuesday, September 18th.

Wednesday, September 12, 2012

That Beyoncé Video WAS Great...

Labels:

as discussed in class,

cultural detritus,

videos

Tuesday, September 11, 2012

Howard Sure Is a Duck

Howard the Duck is my favorite synecdoche for the 80's:

Labels:

as discussed in class,

cultural detritus,

videos

Monday, September 10, 2012

Homework: Email Subscription

So why does this course have a blog? Well, why is anything anything?

A blog is a website that works like a journal – users write posts that are sorted by date based on when they were written. You can find important course information (like assignments, due dates, reading schedules, etc.) on the blog. I’ll also be updating the blog throughout the semester, posting interesting items related to the stuff we’re currently discussing in class. You don't have to visit the blog if you don't want to. It's just a helpful resource. I've used a blog for this course a lot, and it's seemed helpful. Hopefully it can benefit our course, too.

Since I’ll be updating the blog a lot throughout the semester, you should check it frequently. There are, however, some convenient ways to do this without simply going to the blog each day. The best way to do this is by getting an email subscription, so any new blog post I write automatically gets emailed to you. (You can also subscribe to the rss feed, if you know what that means.) To get an email subscription:

1. Go to http://rowanlogic2012.blogspot.com.

2. At the main page, enter your email address at the top of the right column (under “EMAIL SUBSCRIPTION: Enter your Email”) and click the "Subscribe me!" button.

3. This will take you to a new page. Follow the directions under #2, where it says “To help stop spam, please type the text here that you see in the image below. Visually impaired or blind users should contact support by email.” Once you type the text, click the "Subscribe me!" button again.

4. You'll then get an email regarding the blog subscription. (Check your spam folder if you haven’t received an email after a day.) You have to confirm your registration. Do so by clicking on the "Click here to activate your account" link in the email you receive.

5. This will bring you to a page that says "Your subscription is confirmed!" Now you're subscribed.

If you are unsure whether you've subscribed, ask me (609-980-8367; landis@rowan.edu). I can check who's subscribed and who hasn't.

A blog is a website that works like a journal – users write posts that are sorted by date based on when they were written. You can find important course information (like assignments, due dates, reading schedules, etc.) on the blog. I’ll also be updating the blog throughout the semester, posting interesting items related to the stuff we’re currently discussing in class. You don't have to visit the blog if you don't want to. It's just a helpful resource. I've used a blog for this course a lot, and it's seemed helpful. Hopefully it can benefit our course, too.

Since I’ll be updating the blog a lot throughout the semester, you should check it frequently. There are, however, some convenient ways to do this without simply going to the blog each day. The best way to do this is by getting an email subscription, so any new blog post I write automatically gets emailed to you. (You can also subscribe to the rss feed, if you know what that means.) To get an email subscription:

1. Go to http://rowanlogic2012.blogspot.com.

2. At the main page, enter your email address at the top of the right column (under “EMAIL SUBSCRIPTION: Enter your Email”) and click the "Subscribe me!" button.

3. This will take you to a new page. Follow the directions under #2, where it says “To help stop spam, please type the text here that you see in the image below. Visually impaired or blind users should contact support by email.” Once you type the text, click the "Subscribe me!" button again.

4. You'll then get an email regarding the blog subscription. (Check your spam folder if you haven’t received an email after a day.) You have to confirm your registration. Do so by clicking on the "Click here to activate your account" link in the email you receive.

5. This will bring you to a page that says "Your subscription is confirmed!" Now you're subscribed.

If you are unsure whether you've subscribed, ask me (609-980-8367; landis@rowan.edu). I can check who's subscribed and who hasn't.

Thursday, September 6, 2012

Course Details

The Logic of Everyday Reasoning

Rowan University

Philosophy 09110-9

Fall 2012

Tuesdays and Thursdays, 4:45 – 6:00 p.m. in Bunce Hall, Room 109

Rowan University

Philosophy 09110-9

Fall 2012

Tuesdays and Thursdays, 4:45 – 6:00 p.m. in Bunce Hall, Room 109

Email: landis@rowan.edu

Phone: 609-980-8367

Course Website: http://rowanlogic2012.blogspot.com

Office Hours: by appointment

Required Text

THiNK: Critical Thinking and Logic Skills for Everyday Life, 2nd edition, by Judith Boss

We are presented with arguments in support of all sorts of claims all the time, on topics as serious as abortion or the death penalty and as trivial as who the Phillies best player is or whether Conan is funnier than Leno. How can we tell good arguments from bad ones?

This course focuses on understanding and evaluating arguments. We’ll first learn how to identify the components and structures of arguments. We’ll then learn how to pick apart the bad reasoning found in some arguments by going over logical fallacies, which are the different ways an argument can go wrong. We’ll also discuss the limitations of our own reasoning abilities and the natural biases that throw us off.

Armed with these evaluative tools, we’ll then explore our arguments for what we believe, and revise or strengthen them based on proper reasoning. The course’s main goal is to develop a respect for arguments as an important, if not the most important, tool of inquiry and decision-making. Examining the logical evidence in support of a claim or decision is a crucial component of figuring out the truth and gaining a deep understanding of complex issues.

Assignments

Each assignment is created carefully, and designed to both measure and improve upon specific skills that students are expected to develop throughout the semester. I try to explicitly point out the educational importance of each assignment (both below and when I assign it), but if an assignment’s value is ever unclear, let me know! I value student feedback. Sometimes complacency makes me continue using an assignment that isn’t very helpful, or sometimes I haven’t explained an assignment clarly enough.

Midterm and Final Exams: Exams are a chance to demonstrate your understanding of a wide variety of topics and skills that we’ll study throughout the semester. To this end, there will be a variety of question types on the exams. The midterm tests everything covered during the first half of the course, and will last the full period (75 minutes) on the scheduled day. The final exam is cumulative—that is, it tests everything covered throughout the whole course. The final will also last about 75 minutes, and be held during finals week.

Quizzes: Unlike the exams, quizzes will not be cumulative. Quiz #1 will test you on everything covered during the first 4 weeks of class, and quiz #2 will test you on the material we cover after the midterm. Quizzes will last 25 minutes, and be held at the beginning of the period on the scheduled day.

Short Paper: There will be a short paper (400-800 words) on understanding and evaluating an argument from a newspaper or magazine article. Due toward the end of the semester, this assignment provides you with an opportunity to demonstrate whether you have developed two of the most primary skills we’re learning this semester: the ability to understand an argument, and the ability to evaluate an argument’s logical quality.

Group Presentation: This will be a group project presented in front of the class in the middle of the semester. Each group of 3-5 students will research two fallacies and present a 10- to 15-minute oral presentation on them to the rest of the class. Groups should focus on teaching these fallacies effectively. To this end, the main criteria groups shall be graded on are their understanding of the fallacies and their ability to effectively communicate their understanding to the rest of class.

Homework: Although I usually assign a lot of optional extra credit assignments throughout the semester, there will only be three graded homework assignments. These homework assignments will be similar to the various extra credit and in-class group work assignments we do. The graded homeworks, however, will usually come at the end of a particular section, after you have had a chance to try a variety of similar logical assignments in and out of class. The expectation, then, is not that you master every skill or concept as soon as it is introduced. Rather, you should expect to struggle on the informal and extra assignments, using them as important practice for improvement. Only after a lot of practice and effort do I expect you to perform well, and only then shall I grade your performance.

Fun Thursdays: There will be three in-class graded assignments scheduled on some Thursdays during the semester. These will be a chance to more casually discuss some issues more loosely related to the class, yet more closely connected to important practical concerns of our everyday lives.

Attendance/Participation: Most of this will be based on your attendance. If you’re there every class, you’ll get full credit for your attendance grade. In addition, informal group work can impact your grade. I value your attendance, and I expect you to show up each day. I also realize, though, that we sometimes need added motivation to attend each day, and I use this grade as a small carrot to motivate you.

Extra Credit: I like giving extra credit! I’ll be giving some official extra credit assignments throughout the semester. I’ll also be offering some extra credit points more informally during class time. Remind me about this if I slack off on dishing out extra credit points.

Midterm 150 points

Final 250 points

Quizzes (2) 75 points each (150 points total)

Group Presentation 150 points

Homework 90 points total

Short Paper 100 points

Fun Tuesdays 60 points total

Attendance/Participation 50 points

Grades

A = 934-1000 total points

A- = 900-933 total points

B+ = 867-899 total points

B = 834-866 total points

B- = 800-833 total points

C+ = 767-799 total points

C = 734-766 total points

C- = 700-733 total points

D+ = 667-699 total points

D = 634-666 total points

D- = 600-633 total points

F = below 600 total points

Classroom Policies

Academic Integrity: Cheating and plagiarism (using someone else’s words or ideas in a paper or assignment without giving credit to the source) will not be tolerated in the class. Students found guilty of either will definitely fail the exam or assignment on which they plagiarize—and possibly the entire class.

Excused Absences: Make-up exams, quizzes, in-class projects, and oral reports will only be rescheduled for any excused absences. Excused absences include religious observance, official college business, and illness or injury (with a doctor’s note). An unexcused absence on the day of any assignment or test can result in a zero on that assignment or test.

Tuesday, September 4, 2012

Course Schedule

*This schedule is tentative and will probably change a lot*

September 4—6

Tuesday: Introduction to class | (no reading)

Thursday: Critical Thinking & Understanding Arguments| read pages 165-174

September 11—13

Tuesday: Understanding Arguments: Argument Workshop| read pages 174-184

Thursday: Evaluating Arguments | read pages 185-191

September 18—20

Tuesday: Deductive Args: Valid & Sound | read pages 237-247

Thursday: Deductive Args: Evaluating Validity | read pages 247-261; Homework #1 due

September 25—27

Tuesday: Inductive Arguments | read pages 200-213

Thursday: QUIZ #1; Inductive Args: Analogies & Causal Args | read pages 214-227

October 2—4

Tuesday: Inductive Args wrap-up

Thursday: Scientific Reasoning (Abductive Args) | read pages 366-383 | FUN THURSDAY #1: Proof

October 9—11

Tuesday: Scientific Arguments: Evaluation (murder mystery) | read pages 384-394

Thursday: Fallacies: Equivocation, Division, Composition| read pages 131-136

October 16—18

Tuesday: Fallacies: Ad Hominem, Force, Pity, Popular Appeal | pgs. 137-144; Presentations #1 & #2

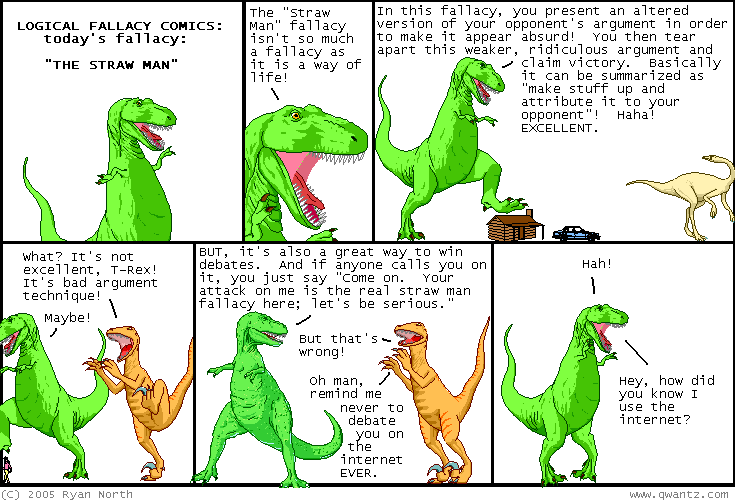

Thursday: Fallacies: Ignorance, Circular, Straw Man, Red Herring | pgs. 144-150; Presentations #3 & #4; Homework #2 due

October 23—25

Tuesday: Review for Midterm Exam | (no assignment)

Thursday: MIDTERM EXAM

October 30—November 1

Tuesday: Fallacies: Authority, Dilemma, Slippery, & Naturalistic | pgs. 150-159; Presentations #5 & #6

Thursday: Cognitive Biases: Perception, Memory, Hearsay | read pages 95-102

November 6—8

Tuesday: Cognitive Biases: Confirmation Bias, Statistical Reasoning | read pages 102-113

Thursday: Cognitive Biases: I’M-SPECIAL-ism | read pages 113-117

November 13—15

Tuesday: Cognitive Biases: Social Biases | read pgs. 118-123

Thursday: Cognitive Biases: wrap-up | no reading | FUN THURSDAY #2: Counteracting Biases

November 20

Tuesday: QUIZ #2; Intellectual Honesty intro | read pages 1-12

Thursday: THANKSGIVING (no class!)

November 27—29

Tuesday: Intellectual Honesty: Charity | read pages 13-19

Thursday: Intellectual Honesty: Humility, Open-Mindedness | pgs. 20-29 | FUN THURSDAY #3: Life Plan

December 4—6

Tuesday: PAPER due; Advertising & News | read pages 309-319, 323-330

Thursday: Mass Media: News, Critical Consumers | read pages 338-352

December 11

Tuesday: Mass Media wrap-up; review for Final Exam | read pages 357-359 | Homework #3 due

December 18

4:50-6:50 FINAL EXAM

September 4—6

Tuesday: Introduction to class | (no reading)

Thursday: Critical Thinking & Understanding Arguments| read pages 165-174

September 11—13

Tuesday: Understanding Arguments: Argument Workshop| read pages 174-184

Thursday: Evaluating Arguments | read pages 185-191

September 18—20

Tuesday: Deductive Args: Valid & Sound | read pages 237-247

Thursday: Deductive Args: Evaluating Validity | read pages 247-261; Homework #1 due

September 25—27

Tuesday: Inductive Arguments | read pages 200-213

Thursday: QUIZ #1; Inductive Args: Analogies & Causal Args | read pages 214-227

October 2—4

Tuesday: Inductive Args wrap-up

Thursday: Scientific Reasoning (Abductive Args) | read pages 366-383 | FUN THURSDAY #1: Proof

October 9—11

Tuesday: Scientific Arguments: Evaluation (murder mystery) | read pages 384-394

Thursday: Fallacies: Equivocation, Division, Composition| read pages 131-136

October 16—18

Tuesday: Fallacies: Ad Hominem, Force, Pity, Popular Appeal | pgs. 137-144; Presentations #1 & #2

Thursday: Fallacies: Ignorance, Circular, Straw Man, Red Herring | pgs. 144-150; Presentations #3 & #4; Homework #2 due

October 23—25

Tuesday: Review for Midterm Exam | (no assignment)

Thursday: MIDTERM EXAM

October 30—November 1

Tuesday: Fallacies: Authority, Dilemma, Slippery, & Naturalistic | pgs. 150-159; Presentations #5 & #6

Thursday: Cognitive Biases: Perception, Memory, Hearsay | read pages 95-102

November 6—8

Tuesday: Cognitive Biases: Confirmation Bias, Statistical Reasoning | read pages 102-113

Thursday: Cognitive Biases: I’M-SPECIAL-ism | read pages 113-117

November 13—15

Tuesday: Cognitive Biases: Social Biases | read pgs. 118-123

Thursday: Cognitive Biases: wrap-up | no reading | FUN THURSDAY #2: Counteracting Biases

November 20

Tuesday: QUIZ #2; Intellectual Honesty intro | read pages 1-12

Thursday: THANKSGIVING (no class!)

November 27—29

Tuesday: Intellectual Honesty: Charity | read pages 13-19

Thursday: Intellectual Honesty: Humility, Open-Mindedness | pgs. 20-29 | FUN THURSDAY #3: Life Plan

December 4—6

Tuesday: PAPER due; Advertising & News | read pages 309-319, 323-330

Thursday: Mass Media: News, Critical Consumers | read pages 338-352

December 11

Tuesday: Mass Media wrap-up; review for Final Exam | read pages 357-359 | Homework #3 due

December 18

4:50-6:50 FINAL EXAM

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)